Writing About Testimony: Is There a World Beyond 'The Witness Further Stated'?

Many lawyers find themselves retelling—or regurgitating—testimony from fact witnesses, expert witnesses, or both. The default mode is often as painful to write as it is to read. A witness “stated that.” And then, in the next sentence, the witness “further stated that.” If the writer is feeling feisty, a few sentences later, the witness no longer “stated that” but . . . “opined that.”

Many lawyers find themselves retelling—or regurgitating—testimony from fact witnesses, expert witnesses, or both. The default mode is often as painful to write as it is to read. A witness “stated that.” And then, in the next sentence, the witness “further stated that.” If the writer is feeling feisty, a few sentences later, the witness no longer “stated that” but . . . “opined that.”

Stop the presses! It’s safe writing for sure. But pairing socks in a sock drawer is safe, too.

Is there a better way? Let’s consider approaches that are too cold, too hot, and perhaps just right.

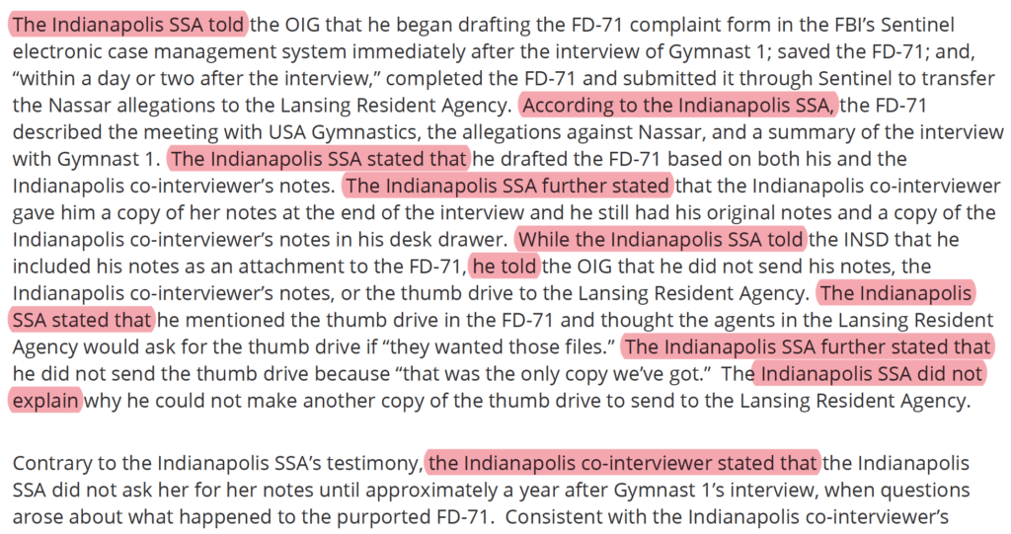

Too Cold? The Inspector General’s Larry Nassar Report

Take the scathing report on the FBI’s investigation of Larry Nassar, the doctor for Team USA gymnastics who pleaded guilty to sexual assault. Page after page of the report consists mainly of one witness after another stating or further stating something:

I do get the appeal of this style: You don’t want to insert yourself into the narrative. You want to stay faithful to the transcripts. And you want to look painstaking and thorough.

But at some point, cautious regurgitation is no longer writing or advocating or even clarifying; it’s rote transcribing. How can even a diligent reader know what to make of dozens of pages of line-by-line recitations from endless interviews?

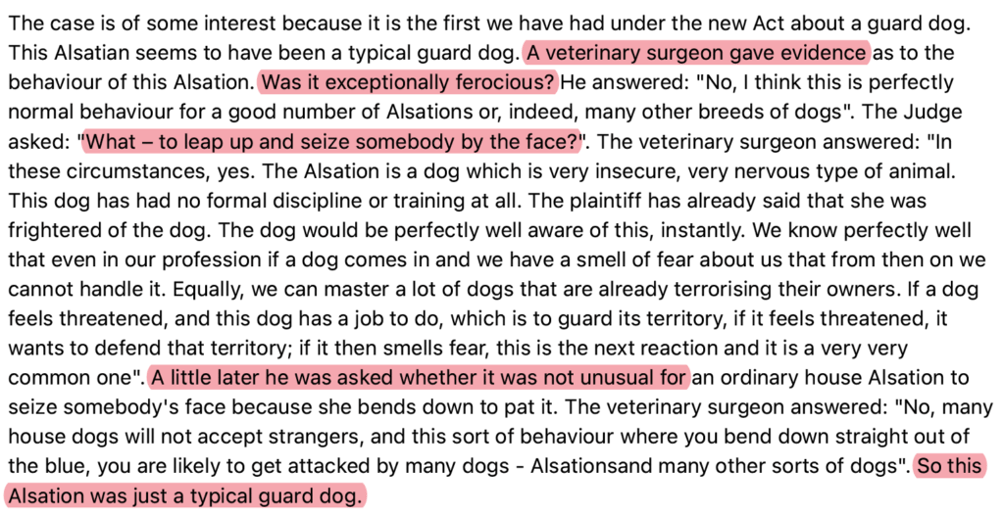

Too Hot? Lord Denning and the Veterinary Surgeon

For an altogether different approach, consider this spectacular passage from Cummings v Granger, the famous judgment that Lord Denning began alliteratively with “This is the case of the barmaid who was badly bitten by a big dog.” Relaying the testimony of an expert veterinary surgeon, Lord Denning combined select quoting, indirect paraphrase, and context cues to convey the essence of the expert’s take in clear and exacting prose:

Let’s not accuse Lord Denning of taking artistic license merely because the passage is easy and enjoyable to read. There’s nothing unfair or even especially rhetorical or subjective here. What’s more, short of acting as a court reporter, you can never relay testimony neutrally: Even if you seek refuge in “he said . . . he further said . . . she said,” you’re still calling shots, whether it’s deciding which points to relay or choosing which of the witness’s words to share.

Of course, Lord Denning’s approach might still seem like a bridge too far. If so, let’s return to the United States.

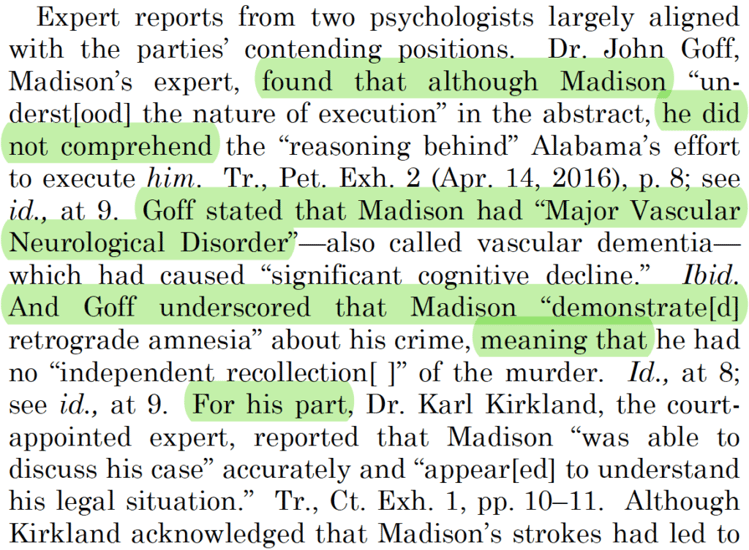

Just Right: Justice Kagan and Justice Thomas

The best strategy combines the best of the two approaches above.

Like Lord Denning, Justice Kagan quotes as little as she can here. She also starts by sharing how the pair of expert testimonies fits into the larger arguments. Even a precise verb like “underscored” helps readers understand what’s what. At the same time, though, Justice Kagan hews much closer to the transcripts than Lord Denning does:

The same is true for Justice Thomas’s strategy below. What’s especially helpful is that once Justice Thomas makes clear that he’s relaying the views of Georgia’s expert, he stays in that voice without compulsively attributing each new point to the same expert: “water would be passed through . . . Florida would receive . . . Data . . . showed . . . .” Florida might contest those conclusions, but no reader would doubt even for a moment which expert had reached them:

Simply put, if Justice Kagan and Justice Thomas share a writing technique, you probably can’t go wrong. The next time you recount witness testimony, remember that half a voice is better than none.

By

By