Five Ways to Write Like Justice Scalia

Who are the best writers in Supreme Court history? Poll a hundred lawyers, and just about all of them will put the late Justice Antonin Scalia in their top five. Some may quibble with his judicial philosophy, but no one can question Justice Scalia’s writing chops.

To see why, we need look no further than his famous dissenting opinion in Morrison v. Olson. The majority upheld the constitutionality of the Independent Counsel Act, which obliged the Attorney General to recommend the appointment of a special prosecutor whenever Congress turned up dirt on an executive-branch official. Justice Scalia, gravely concerned with the Act’s constitutional consequences, objected to the majority’s view, penning a dissent that turned unitary executive theory into high art.

1. Long in the Tooth—Show That It’s Always Been This Way

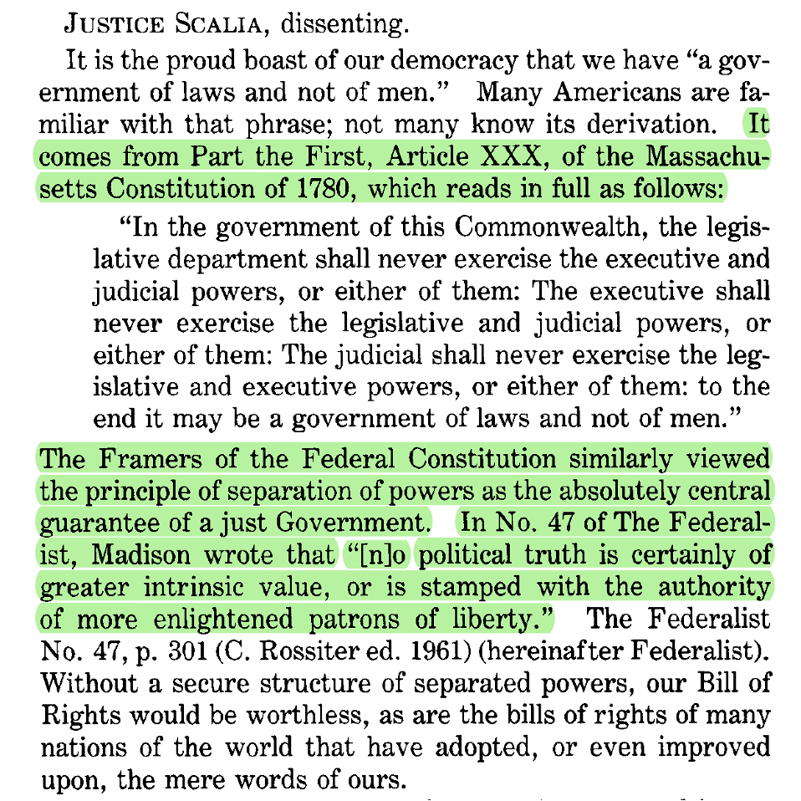

A conservative in every sense of the word, Justice Scalia liked his law served tried and true, with a long and venerable pedigree—the longer, in fact, the better. When the Constitution was at stake, as it was in Morrison, eighteenth-century texts were best. And if those texts were written by one of the Founding Fathers, well, Point Made.

A conservative in every sense of the word, Justice Scalia liked his law served tried and true, with a long and venerable pedigree—the longer, in fact, the better. When the Constitution was at stake, as it was in Morrison, eighteenth-century texts were best. And if those texts were written by one of the Founding Fathers, well, Point Made.

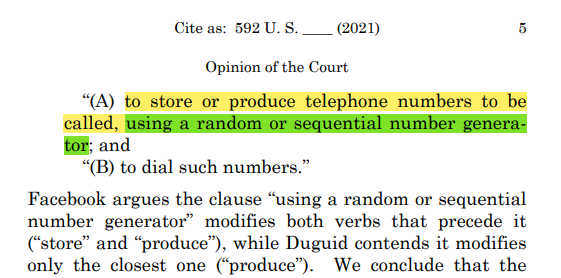

Take the opening of his Morrison dissent. In under a page, Justice Scalia quotes first from a Revolutionary-era state constitution (John Adams), then from Federalist 47 (James Madison)—a President per paragraph:

2. Back to Life—Center Technical Matter on People or Entities

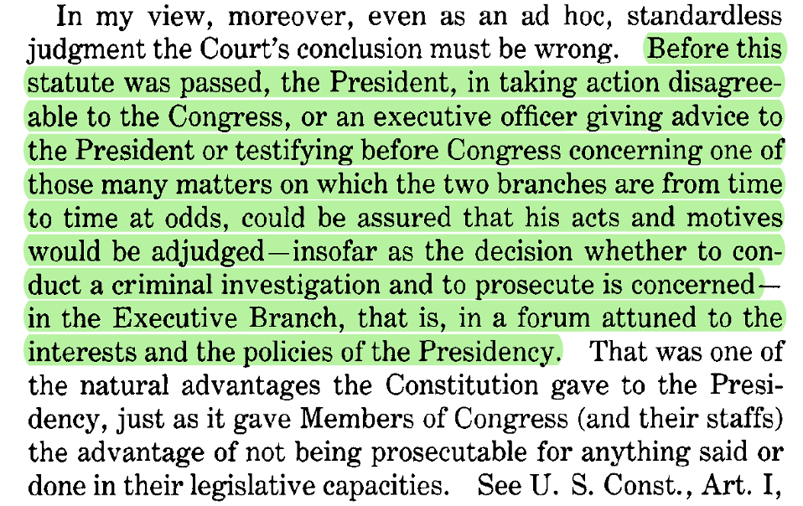

Scalia’s greatest strength as a writer may have been his ability to transform complex and abstract legal issues into the stuff of high drama. Watch, for instance, how swiftly he turns a lawsuit about a statute’s validity into a power struggle between two branches of government:

The Legislative and Executive Branches appear in different guises throughout the dissent—the House of Representatives vs. the EPA, a House Subcommittee vs. the Attorney General, Congress vs. the DOJ—but always as characters at odds with one another in the same play. They can “haggle,” “reach agreement,” or even get angry:

3. What a Breeze—Write with a Confident Tone

Scalia is justifiably famous for his quick turns of phrase and verbal barbs, but he’s never clever just for the sake of being clever: his wit is always in service of the reader. Here, he employs a memorable comparison to rebut the notion that limits on the scope of the independent counsel’s jurisdiction excuse her arrogation of executive power:

4. Manner of Speaking—Use Figures of Speech

4. Manner of Speaking—Use Figures of Speech

Justice Scalia enlivened his opinions not only by personifying abstract ideas, but also by deploying vivid and imaginative figures of speech. Although his sharp-witted rhetorical flourishes could sometimes verge on insult (don’t try this in court), they always left the reader with an unforgettable image that drove his point home.

Here, with his famous understatement, Scalia uses simile to show why he finds the majority’s view absurd:

5. Jumpstart Your Sentences—Vary Your Sentence Length

5. Jumpstart Your Sentences—Vary Your Sentence Length

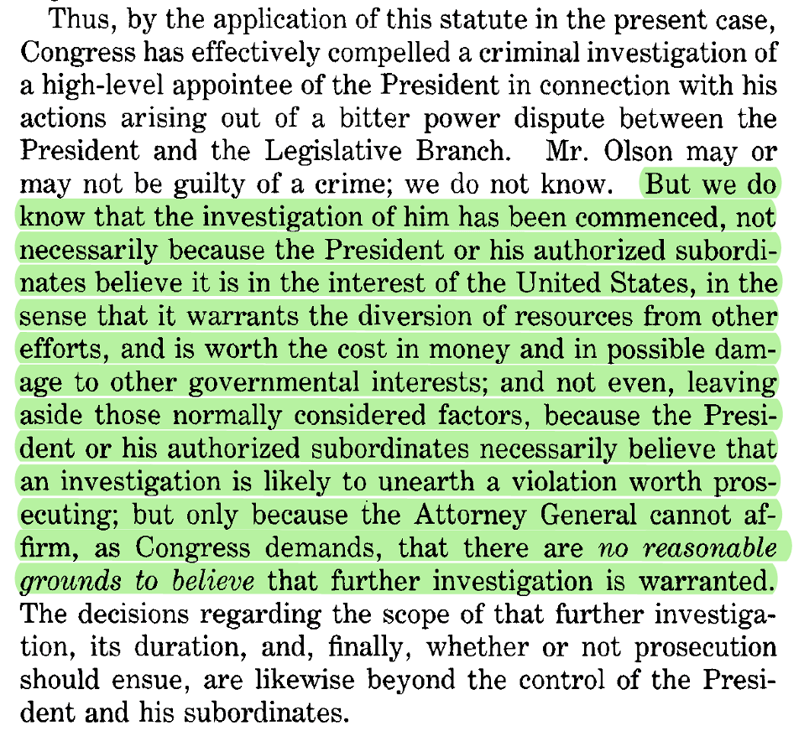

In Point Made, I describe a range of techniques for livening up your sentences. Among my favorites are the sentence that starts with a one-syllable opener like “but” or “nor,” the clever pithy sentence, and—conversely—the long, elegant sentence. Justice Scalia is a master of all three, but his meticulously constructed long sentences are in a league of their own. Take this one:

Of course, Justice Scalia could have just called the independent-counsel statute flimsy and dangerous; but his gracefully stacked clauses and balanced phrases make the point much more convincing and memorable.

And even when he packs a great deal of material into a single sentence, Justice Scalia never loses sight of the theme. To the contrary, each of the 92 words in this sentence drives home the statute’s threat to executive independence:

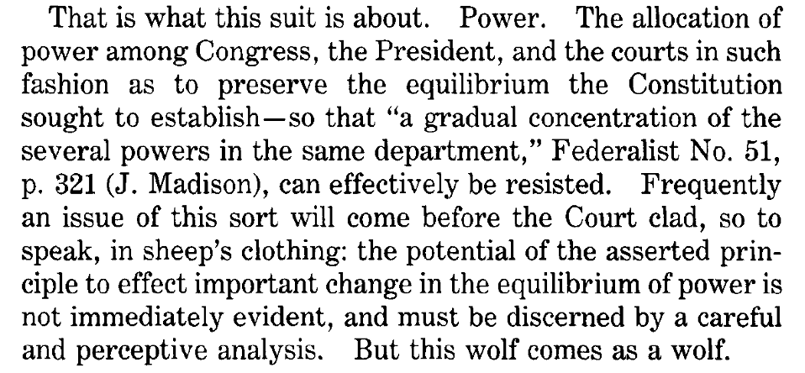

Let’s look at one last excerpt from the Morrison dissent to see how Justice Scalia earned his top spot among the Court’s greatest writers. In a short, masterful paragraph that’s become one of the most famous passages in all judicial opinion writing, Scalia packs all five of the techniques we’ve discussed (and more) into little more than a hundred words. He writes confidently, with a conversational tone that sounds almost like dialogue; flanks two elegant sentences (and even bolder, a fragment) with short, pithy ones; weaves in another quote from Madison; brings the case’s characters to life; and ends with an astounding metaphor to show us why we should fear the majority’s decision:

In 1999, Congress voted to let the Independent Counsel Act lapse. Did Scalia’s writing have anything to do with it? You bet.

By

By