Textualism Whiplash: Two Supreme Studies

“We are all textualists now,” said Justice Kagan at a speech honoring Justice Scalia. The Justices all agree on that much. But then what?

In 2016, the Supreme Court had to decide whether “involving a minor” limited just the third type of crime below or the other two types as well.

That case was Lockhart v. United States.

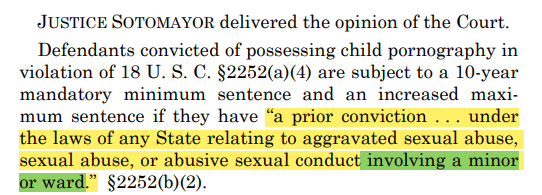

Five years later, the Supreme Court decided whether “using a random or sequential number generator” limited just “produce”—or did it limit “store,” too?

That case is Facebook v. Diguid.

In 2016, the Court, in a 7-2 opinion by Justice Sotomayor, began its analysis with “Consider the text.”

In 2021, the Court, in a 9-0 opinion by Justice Sotomayor, started its analysis with “We begin with the text.”

But then . . . all heck breaks loose.

The 2016 Lockhart Majority

A summary of the “method”:

The doctrine of the last antecedent says that “involving a minor” modifies only the last of the items on the list.

The statutory phrase functions a bit like this: “a defensive catcher, a quick-footed shortstop, or a pitcher from last year’s World Champion Kansas City Royals.” Everyone hearing that phrase would know that the pitcher must hale from the Royals while the catcher and the shortstop need not.

That said, the last-antecedent rule isn’t absolute. “Other indicia of meaning” can trump it. Sometimes.

At the same time, the good news is that our last-antecedent-based reading also makes good sense! Just look at other parts of the Criminal Code—the similarity between the “involving a minor” provision and other criminal statutes must be “more than a coincidence.”

Sure, in other statutory cases we have invoked other canons, like the series-qualifier principle, which would admittedly yield the opposite result here. It’s a perfectly decent canon, but it’s not quite “a countervailing grammatical mandate.” At least not here.

Not to mention that applying the “involving a minor” phrase to just the third type of crimes would help save the statute from itself: It affords us just the right degree of redundancy between the three predicate state crimes, making them different enough from one another but not too different.

In any event, we can’t really interpret the meaning of this provision in light of “how people ordinarily speak and write.” After all, the statute has “odd repetition and inelegant phrasing,” so it’s not like “everyday” speech. Not even the speech of “an average lawyer.” So the plain meaning of the statute has to derive from . . . some other source. (Editorial hypothesis: the speech of an above-average lawyer?)

The 2021 Facebook Majority

A summary of the “method”:

The series-qualifier canon (not, this time, the doctrine of the last antecedent) “generally reflects the most natural reading of a sentence.”

If a teacher said that “students must not complete or check any homework to be turned in for a grade, using online homework-help websites,” the modifying phrase applies to both “complete” and “check,” not just “check.”

Plus the language that comes before the modifier is “concise, integrated.”

Not to mention the comma before “using.” That comma suggests that the modifier modifies both store and produce, not just produce.

Now it’s true that we did invoke the doctrine of the last antecedent in Lockhart. But that doctrine is . . . “context dependent.”

What’s more, any other reading “would take a chainsaw” to the problem Congress was solving when it only “meant to use a scalpel.”

The opposite reading still might have “some appeal,” of course, but only if our reading were “contextually implausible.”

By the way, as far as legislative history, Congress seemed concerned about telemarketing, but not THAT concerned.

Good thing we’re around to interpret what Congress writes.

A good thing indeed. How could anyone else step in?

By

By